St Agatha's wall paintings

The series of murals in St. Agatha's church Easby is a picture-story of God, his covenant with all humanity throughout all time.

The wall paintings in St. Agatha's Church, Easby, which date from around 1250 AD, were discovered during the Victorian restoration of the church, and were restored in 1994 by Perry Lithgow, supported by a grant from English Heritage. They had been covered with lime-wash during the sixteenth century Reformation, probably during the reign of Edward VI, son of Henry VIII. This was in order to obliterate anything deemed to be 'childish superstition'. The paradox of this, of course, is the attempt to remove them actually resulted in their survival, because paintings such as these were never meant to be permanent, but rather replaced when they had deteriorated or become outdated (Rouse, page 9).

Who were the painters? Sadly, they are unknown for Easby as they are for most village churches. They were probably journeymen, who travelled from place to place. The technique used in England was to cover the entire surface to be painted with plaster, after which it was finished with a coat of lime-putty. Colours were made from mixing iron oxides, the commonest of which were red and yellow ochres, within which a wide range of shades was possible. Blue was rarely used, but a skilful mixing of black and white with prime colours could produce a wide colour range.

The Easby murals are significant for several reasons, including they are of an early date, c 1250 A.D., and also because they were painted during the pivotal time of the thirteenth century when the focus of teaching Christian doctrine moved from the Roman focus of Christ as Judge to Christ the Redeemer (Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, page 299). This is exactly what the murals at Easby symbolise.

During the medieval period murals were to be found in most parish churches, although the majority have not survived. Their purpose wasn't merely to decorate the building, but to illustrate for people the Christian message, as interpreted at that time from scripture, and probably even to reinforce the Christian message delivered during worship.

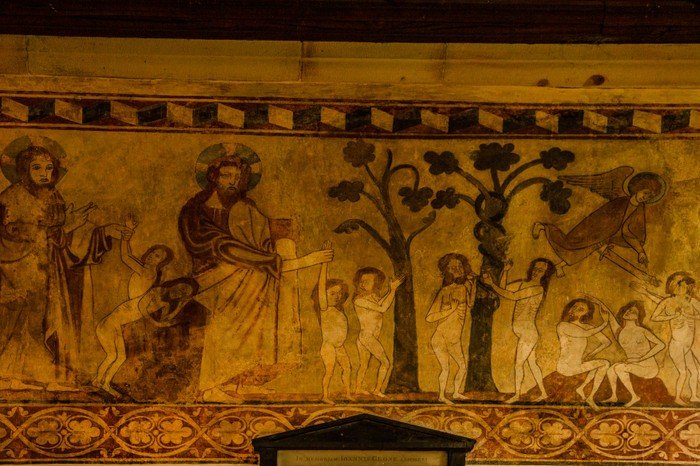

The Easby murals follow a conventional pattern for wall paintings, in that the Biblical narratives they depict are shown in a 'comic strip' arrangement, reading from left to right, beginning with the Old Testament scenes on the north wall of the chancel.

Vulnerability is the first thought which perhaps strikes first – the figures are unclothed. Although adult, they are delicate and full of potential and movement. The use of nakedness was an artistic convention – naked figures depicted the human soul, rather than a physical body, with rank shown by crowns, mitres or, as at Easby, the lowest rank of all, the peasant without adornment (E. Clive Rouse, page 17), At least three parts to the message of The Fall (Genesis, chapters 2/3 ) are shown here. In the first, the human figure of God, as a male father figure, is leading Adam and Eve to the Garden of Eden.

The hint of something sinister lurking around is hinted at by the image of a serpent coiling around the trunk of the tree of knowledge. Vulnerability is all around.

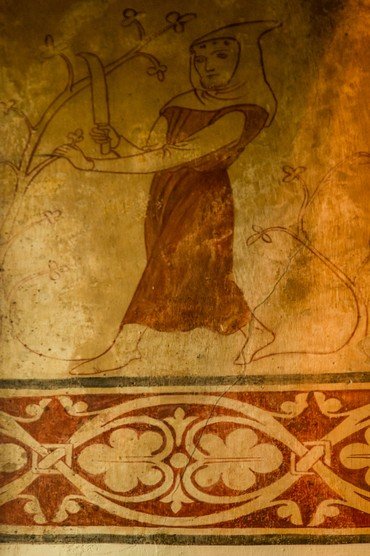

The pictures continue by showing scenes of the expulsion from the Garden of Eden, or Paradise. The result of the expulsion from Paradise is shown by people hard at work, tied to the agricultural cycle of labour. They wear costume contemporary to the time of the paintings to aid recognition of their status, a further artistic convention (Rouse page 18). This also provides, inadvertently, a means of dating the paintings. Originally, in the medieval period, there would have been twelve such scenes, representing the work of each month in the year. The sower is a medieval peasant, bound to the earth in that he is tied to labours of the agricultural cycle. Even as he spreads valuable seed, he is shadowed by a crow, ever ready to steal and devour seed and thus diminish the crop.

Likewise the woman pruning cannot escape the never ending task of trimming the growing crop to encourage a good harvest.

Notice, however, the suggestion God, shown as a father-figure, has not abandoned the human race, for the labourers are receiving comfort as they work.

Gardeners will recognise the fatigue felt by the labourers digging hard into the earth as they prepare the soil for the following seed time and the painting of hawking, representing some light relief which would doubtlessly be welcome!

Turning to the series of paintings on the south wall of the chancel, the theme of the Fall is developed by linking it with the doctrine of The Salvation through the birth and passion of Jesus of Nazareth (for example, Luke, chapters 1/2 and 27/28) beginning with a mural of The Annunciation. Mary is shown in reflective mood by an urn of lilies, an image of purity. This is The Annunciation to Mary that she will give birth to a son, who will be very special (Luke Chapter 1).

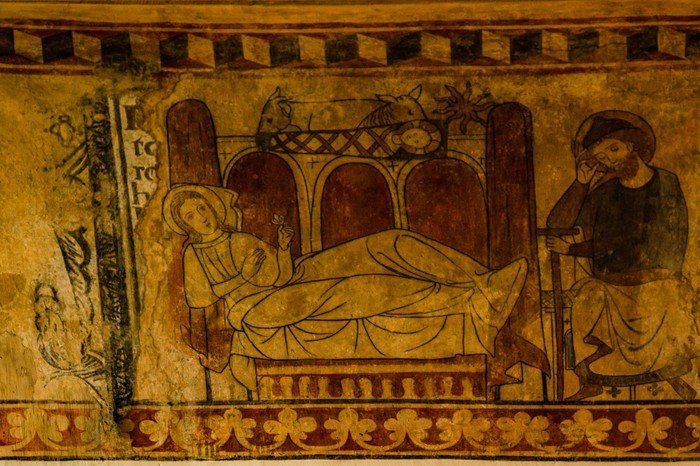

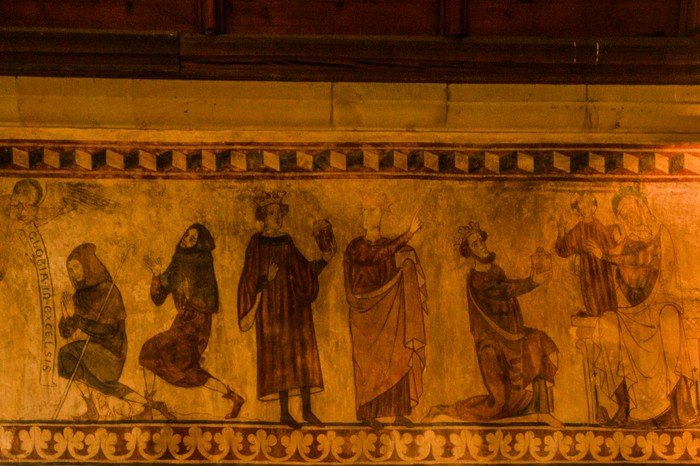

The Nativity, or the birth of Jesus of Nazareth follows – it is an unusual depiction of the well-known narrative with humorous flashes. The baby, in swaddling clothes, is lying on top of arches, with two beasts above. Mary, who has just given birth, is recumbent on the floor, looking quite composed. Conversely, it is Joseph who looks weary as he leans on a stick, head resting on his hand. The coming of light to a dark world is symbolised by the Star of Bethlehem. The scene of the birth is one of poverty. The first to hear the news of the birth are poor shepherds, depicted above in the frieze, as are the kings, a little further along.

In spite of the early promise embodied in the narrative of the Nativity, the earthly life of Jesus ended in a savage death – through crucifixion, a commonly used method of execution by the Romans. The mural depicting the removal of Jesus' body from the cross is full of movement – it is easy to be drawn visually into the group of people in medieval costume who swarm around the cross, supporting the body as it is lowered to the ground.

The scene shows the aftermath of extreme cruelty. On the right, one figure already has available a cask, possibly holding ointment for the anointing of the body. This is one of the last things Jesus' followers could do for him.

The scene of Jesus in the tomb, undergoing anointment, is reminiscent of the Nativity picture – just as the helpless baby lay above arches then, so now does the lifeless body. Does this suggest a new, second birth? Or just hopelessness in the face of physical death?

To the right of the mural is a scene showing an empty tomb with the figure of the angel proclaiming the resurrection. The artist struggles to communicate the notion of something as unlikely as the resurrection of a dead body.

What teachings might these murals be attempting to convey? The following is my personal interpretation. The figures of Adam and Eve symbolise the inner workings of the human soul, or mind, which hovers between vulnerability and temptation to wilfulness on one hand, and attempts to follow the will of God (that is understanding God as a personification of the force for good in the world) on another. Wilfulness cannot be ignored, nevertheless, which is why God became incarnate, or manifest, in Jesus of Nazareth, ready to sacrifice his life in order to show his overwhelming love for all people, rather than succumb to sin.

Over the years as I have reflected on these paintings, attempting to read them, it suddenly occurred to me that they have had the effect of reading me! In other words, as I have struggled to make sense of what message they could be carrying, they have helped me become aware of my own values – enthusiasms, maybe prejudice, lack of knowledge and a wish to learn more, among many others. Perhaps this is an immensely important function of all art? The result has been, for me, to see not the medieval peasants in the murals but myself and others of my own time, faced with the multitudes of temptations which challenge our values daily – materialism, consumerism, scientism and many others besides. In a sense, I see all humans as Adam and Eve and the toiling medieval peasants, as well as people of the second millennium who continue having to grapple with temptations. A comfort is the thought that the force for good, or positive values, called God, is all around us, empowering resistance – if it is chosen, for we all have free will - to temptation and evil. Therefore, the message spelt out by the Easby murals is relevant to all, irrespective of the age in which we happen to be living.

I have found numerous visits to the wall paintings in St. Agatha's Church at Easby very helpful over many years, and would welcome discussion with others who share in the fascination they stir.

Dr. Elizabeth Ashton

Email - shiremoor30@talktalk.net

REFERENCES AND SUGGESTED FURTHER READING.

Le Ladurie, Emmanuel Roy, (1980 edition) Montaillou, (London: Penguin).

Rouse, E. Clive, (1991 edition) Medieval Wall Paintings (Princes Risborough: Shire Publications).